Reasons Why the Government Should Give More Money to Arts

P lease God, no. Over 60 years subsequently the foundation of the Arts Council, 50 years later on the creation of the RSC, with publicly funded British plays the toast of Broadway, visits to newly free museums doubling in a decade and British concert life the envy of the globe, surely nosotros don't take to justify giving public money to the arts? Again?

Well, yes, nosotros do. Despite the civilization government minister Ed Vaizey's insistence that the thirty% cut in the Arts Council's upkeep is a temporary expedient, many of his Conservative colleagues consider any public funding of the arts a course of m larceny. Ivan Lewis, Labour's former civilization spokesman, acknowledges that the case for the arts is yet to be won even within his party; and the new arts spokesman, Dan Jarvis, sees quantifying the value of the arts as one of his most urgent priorities. In the zero-sum economy of austerity Britain, the arts are increasingly required to couch their case in terms advisable to those basic services – social care, education, policing – with which they're in competition for dwindling public funds.

It wasn't always like this. When information technology was founded in 1946, the Arts Council could justify its activities in its own terms: it was there to widen access to the arts throughout the land, likewise as to maintain and develop national arts institutions in the uppercase. Behind the latter policy lay a theory of creative value that yous could call patrician: art's purpose as ennobling, its realm the nation, its organisational form the establishment, its repertoire the established catechism and works aspiring to join it. In this the council was seeking to reverse a ascent tide of populism (fine art's role equally amusement, its realm the marketplace, its course the business organisation, its audience mass), a goal summed up in the founding chairman John Maynard Keynes'south ringing declaration: "Death to Hollywood."

Over the following thirty years, this view of the value of the arts came nether attack, not from the market place but from artists who were artistically and frequently politically oppositional. In the theatre in the late 1950s, on the BBC in the early to mid 1960s, and pretty much everywhere from 1968, patrician arts institutions were challenged and in many cases transformed by those who believed the arts weren't at that place to elevate or divert, but to provoke.

What both the patrician and the provocative shared was a master concern for the people making the art. During the 80s, in the arts as in and so many other spheres of life, Margaret Thatcher sought to shift power from the producer to the consumer, using the market to disempower the provocative (from political theatre groups to the high avant garde) in favour of the populist. This was seen nigh conspicuously in the cluster of forms that defined the cultural 80s. Popular in form and patrician in content, the heritage industry was cultural Thatcherism, promoting (equally the then secretary of land for national heritage, Virginia Bottomley, put it in May 1996) "our country, our cultural heritage and our tourist trade".

In this context, the major justification for regime arts funding became its contribution both to that trade and to trade in general, a case based on the mounting show of the economic value of the arts to the so-called leisure industries, and thereby to the regeneration of Uk's post-industrial cities. This argument was clearly bonny to the (largely) Labour councillors running such cities in the 1980s. The equally appealing idea of the arts as part of the "creative industries" was taken upwards past New Labour's offset culture secretary, Chris Smith, who fix two further objectives for arts policy: that access to the arts should be widened, and that they should contribute to the government's social objectives, particularly urban regeneration and combating social exclusion.

A real alternative to heritage and populism, New Labour'south arts policy had dramatic outcomes in making entrance to museums gratuitous, increasing subsidy to regional theatre and widening access. But at that place were growing grumbles about the social instrumentalism that went with it. Virtually the first thing Nicholas Hytner wrote as the new manager of the National Theatre was a peroration against "a relentless and sectional focus on the nature of our audience". At the aforementioned time as Ofsted'southward Peter Muschamp praised theatre groups for "enabling pupils to discuss and explore complex social issues such equally bullying", members of those groups were existence driven crazy past local government' demands that plays most bullying (or racism or Aids awareness) had happy endings. Critics from the right – such as Munira Mirza of the thinktank Policy Substitution – challenged the statistical testify for the social benefits of the arts and inquired whether arts organisations that didn't see regime-imposed social targets would lose their grants.

By 2004, such critics had gained an unexpected ally, when Chris Smith's successor as civilisation secretary, Tessa Jowell, wrote a paper arguing that instrumentalism devalued the arts' primary purpose, which is to communicate perceptions most the human condition that can't exist communicated in whatsoever other mode. In 2007, Jowell's successor, James Purnell, proudly announced the end of "targetology", and commissioned a report from the former Edinburgh festival director Sir Brian McMaster, which sought to wrest power back from the arts consumer, under the imprint of "excellence". At final, the creative person and the fine art were to be back in command.

Sadly, McMaster failed to reckon with the recession, the deficit and a consequent pressure to justify arts spending in terms comparable to those used to defend threatened social and educational services. A vast array of studies and reports accept been produced over the last v years – some by government bodies, many by independent retrieve tanks – arguing that the arts can't hide behind grandiose rhetoric but must demonstrate the quantifiable value they provide to the public which pays for them.

What adept are the arts?

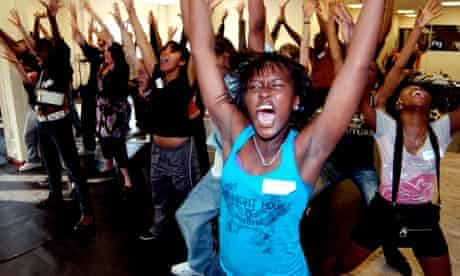

Some of the arguments have been around before. London's commercial theatre earns over half a billion pounds a year; the Young Vic'due south creative director, David Lan, found that 75% of the directors, designers and writers working in the Due west End came from the publically funded theatre, demonstrating its contribution to one of the uppercase'south most obvious tourist attractions. In addition, there is mounting proof of the social value of the arts: even Mirza acknowledges that at that place is "compelling prove" for the benefits of arts participation in the treatment of mental wellness patients. And John Carey – whose 2004 volume What Skillful Are the Arts? is a 300-page philippic confronting the arts having any educative role whatsoever – finds himself impressed by the success of arts activities in edifice cocky-conviction and self-esteem amid young prisoners. A contempo Europe-wide study of five,000 xiii- to 16-year-olds institute that drama in schools significantly increases teenagers' capacity to communicate and to learn, to relate to each other and to tolerate minorities, too as making them more likely to vote (past contrast, those who didn't do drama were likelier to watch television receiver and play computer games).

Increasingly, such benefits are presented non as happy byproducts of artistic activity (and therefore able to be provided by other agencies more price-finer) but as part of its very essence. Five years agone, the Arts Council set out to produce a threefold definition of fine art's purpose: to increase people'southward capacity for life (helping them to "empathize, interpret and adapt to the world around them"), to enrich their experience (bringing "color, beauty, passion and intensity to lives") and to provide a safe site in which they could build their skills, confidence and self-esteem. Other forms of attempt do some of these things. Merely art does all three.

This is a persuasive argument. But, in the electric current climate, the arts are required to show that they're doing this for people not conveniently assembled in schools, hospitals and prisons, in a manner that accords with the Treasury's methods of assessing how other regime activities achieve their objectives. Hence a desperate scrabble around value measurement methodologies (some drawn from healthcare, others from the property market) to try to find mechanisms appropriate to calculating the value of visiting fine art galleries or the opera. So a technique called contingent valuation finds out (through an opinion poll) what people would exist prepared to pay for a particular good or service if information technology weren't provided free, "valuing" diverse cultural institutions, from Irish public dissemination via Durham Cathedral to the British Library (whose services provided £363m of notional value for a funding outlay of £83m). Such hypothetical exercises are – to put it mildly – vulnerable to the proffer that respondents might exaggerate what they'd pay for services that are clearly a good matter and currently free.

There's another problem. About all the documented social benefits of the arts have been accomplished non by people attending plays and concerts but past those who participate in them. And while many publicly funded arts organisations have participatory programmes, most public coin still goes to subsidise people sitting or standing silently looking at other people do things (or, in the case of books and pictures, things they've done). Unless the electric current balance of arts funding between – say – the London Symphony Orchestra and Burnley Youth Theatre is to be reversed, most public funding will go on to go to activities whose value is hardest to measure out.

Hence a movement within the arts to attempt to brand spectatorship every bit involving and transforming as participation. Already, much thought has been devoted to democratising the processes past which professional person art is produced. This is not just a matter of audiences responding to what they run across through surveys, blogs and the like, though this can and should have a existent consequence on how piece of work is curated. The Young Vic and the Almeida are examples of theatre companies whose outreach programmes are designed to involve young people both as participants and audience members. Graham Vick's Birmingham Opera Visitor integrates professional person singers and musicians with community performers who reflect the metropolis'due south diversity and who bring an equally diverse audience with them. In that location is increasing public involvement in the commissioning of public fine art. Inquiry into the National Theatre's NT Live plant that audiences who saw the simultaneous cinema broadcasts of its performances of Phèdre and All's Well that Ends Well found the shows more than emotionally engaging than the theatre audiences, and said information technology would make them more rather than less probable to visit the National Theatre itself as a effect. Empowering the audience would accost the tension between the interests of producers and consumers that has bedevilled arts policy for nearly 70 years.

Such empowerment doesn't have to be bourgeois. If it's true that arts participation makes young people more probable to vote later on, then it should likewise make them more disquisitional. I frequent argument for funding the arts is their office in promoting continuity with the past, community cohesion and a sense of national pride. In fact, of form, British theatre in particular has been subverting such notions always since the emergence of John Osborne, Arnold Wesker and Joan Littlewood nearly 60 years ago. It is this provocative mission that sets the arts apart from the other artistic industries with which they are too easily lumped (by government and opposition alike). Information technology is not the office of advertisers, architects, antique sellers, computer game manufacturers or fashion designers to challenge the way guild is run. But the arts do it all the time. As David Lan puts it, dissent is necessary to republic, and democratic governments should have an interest in preserving sites in which that dissent tin can exist expressed.

When the cuts start to bite …

For me, however, the most compelling argument for funding the arts is non factual just counterfactual. The cuts which beginning biting in April will accept major and notwithstanding unpredictable effects on arts provision in England. Unless the National Theatre, Walsall's New Art Gallery, Battersea Arts Centre, Sadler's Wells and Cardboard Citizens are all profligately run, or the prospects for private patronage accept been scandalously underestimated, then a failure to win the argument for continued public funding – even at reduced levels – would lead to the closure of the nifty majority of currently funded arts organisations, specially outside London. Even if some London flagships survive, they would be unable to continue the very participatory projects that are existence urged on them and to which they are increasingly committed. Would any authorities really want to be the one that closed the Ikon Gallery, DanceXchange, Manchester's Royal Commutation, Graeae or Opera North?

David Edgar'south play Written on the Center is currently running at the RSC'due south Swan Theatre in Stratford.

Source: https://www.theguardian.com/culture/2012/jan/05/david-edgar-why-fund-the-arts

0 Response to "Reasons Why the Government Should Give More Money to Arts"

Post a Comment